Search

“Have you thought about doing the GSBI program,” Dan Kreps asked me after hearing my investor pitch last fall. Indeed, I had considered business accelerators and the Global Social Benefit Institute (GSBI) was certainly on my radar.

“I’m not sure if an accelerator is right for us,” I explained to Kreps, chairman of impact investment firm Advance Global Capital. “After all, we have been selling our field service management software for two years. We have more than 50 customers using us in 38 countries today. We aren’t trying to take an idea from a whiteboard and turn it into reality.”

Launched by Grameen Foundation, TaroWorks had evolved from a social enterprise providing field teams in emerging markets with a mobile data collection and analysis app, to a more robust collection of tools also used to manage remote sales agent networks, direct rural supply chains and generate business insights from a cloud database in real-time.

“You should think about it,” Kreps replied. “The GSBI would be perfect for you right now.”

Image: GSBI social business accelerator program participant presents his business to potential investors. Source: Santa Clara University’s Miller Center for Social Entrepreneurship

In hindsight, my reluctance was partly my ego talking. Before joining TaroWorks as its CEO, I spent two years earning an MBA degree and worked at three tech startups. Did I really need to go back to school to learn how to raise the investment capital needed to fuel growth? Hadn’t I checked that box already?

I also thought that an accelerator for social entrepreneurs would focus too much on the “social” and not enough on the “enterprise.” The most successful social entrepreneurs that I know like Ben Lyon, Hilary Miller-Wise, or Lesley Marincola concentrate on building a business first and foremost. You’re not going to do any good for anyone if you don’t figure out how to stay in business.

Then again, Ben and Lesley are GSBI alumni as is Esoko and three of TaroWorks’ most sophisticated customers: Iluméxico, Sistema.bio and Solar Sister.

Perhaps I should take a deeper look?

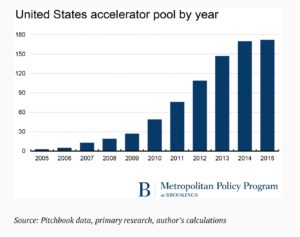

In 2005, Silicon Valley-based Y Combinator launched the first “seed accelerator program” in Boston, according to Ian Hathaway, a nonresident senior fellow in the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program, who tracked the growth of business accelerators in a 2016 Harvard Business Review article.

“Growth in U.S.-based accelerators really took off after 2008, as it did for startups, early-stage capital, and venture investment more broadly. The number of U.S.-based accelerators increased by an average of 50 percent each year between 2008 and 2014.

I was able to identify 172 U.S.-based accelerators in existence during the 2005–2015 period. Collectively, they invested in more than 5,000 U.S. startups. During this period, these companies have raised a total of $19.5 billion in funding, a number that will surely increase as accelerator programs continue to turn out companies and recent graduates work their way to maturity.” (Read More: Here and here)

Internationally, a network of business accelerators has taken root in Latin America, Europe, the African Continent and Asia over the last decade. It’s gotten to the point where university-linked business accelerators and incubators are now benchmarked and there’s even a tool to help select business accelerators that are right for your organization.

Early-stage companies are drawn to business accelerators for what they hope will be a variety of benefits including, “network development (e.g., with potential partners and customers), access and connections to potential investors/funders, mentorship from business experts (and) securing direct venture funding (e.g., grants or investments),” according to Emory University’s comprehensive 2017 Year-End Data Summary of 13,495 ventures, whose founders applied through more than 175 different business accelerators and other entrepreneur support programs.

Among the industry sectors with the largest share of business accelerator participants in Emory University’s sample were education, agriculture, health, information and communication technologies and financial services. Equity investments for these accelerator participants were most common in the financial services sector even though that sector was also the least likely to report earning revenues. On the other hand, the data showed the “greatest incidence of reported revenue generators” was the “artisanal” sector, which was also the most likely to report hiring employees.

There’s a growing body of research attempting to determine whether business accelerators give startup and early-stage businesses the shot needed for them to grow and prosper.

Two findings were particularly interesting to me, from Emory and GALI, respectively:

“Follow-up survey data (from 3,130 ventures) indicate that ventures participating in accelerator programs grow revenues and employees, as well as equity investment and philanthropic contributions, faster than those not accepted into programs. The equity and employee effects are significant.“ (Read More)

“Despite the numerous difficulties of running a startup in emerging market countries, accelerated ventures are often able to grow at similar rates to their counterparts in the United States and Canada. The average effects of acceleration on equity and debt raised were nearly identical in high-income countries and emerging markets, and emerging market ventures were just as likely to report rapid growth.” (Read More)

Source: The Global Accelerator Learning Initiative (GALI)

Echoing Krep’s advice, some data points suggest that established businesses like ours might actually get more out of one of the business accelerators than we would if we were just starting out. The Emory University study, for example, showed that accelerator cohort members “… with prior accelerator experience are significantly better in terms of attracting outside equity (22.6 percent versus 12.0 percent). They are also significantly better when it comes to revenue generation (51.8 percent versus 41.7 percent) and hiring employees (67.5 percent versus 56.1 percent). Finally, the ventures with prior accelerator experience are significantly more likely to report prior philanthropic support (36.1 percent versus 19.5 percent).”

As the number of incubators and accelerators has grown, entrepreneurs have more options. Some accelerators now specialize in growth-stage support, rather than seed stage or concept incubation. Like children, startups face different challenges at different stages of their growth and development. There are now later-stage accelerator options for organizations like TaroWorks that have a tested business model and are ready to scale.

In the end, I decided to apply to the GSBI, which is managed by Santa Clara University’s Miller Center for Social Entrepreneurship, for three reasons:

Source: Santa Clara University’s Miller Center for Social Entrepreneurship

Source: Santa Clara University’s Miller Center for Social Entrepreneurship

In the end, we felt honored that the Miller Center selected TaroWorks along with the likes of Suyo, EarthSpark and 16 others. It wasn’t easy – more than 350 organizations applied.

Cassandra Staff, chief operating officer of the Miller Center, had this advice for us as we embarked on the experience:

“You should be willing to find and address the gaps in your organization that will prevent growth and you need to be open to lots of critical feedback. In return, we’ll make sure that feedback is informed, data-driven and based off of the collective experiences of the hundreds of social enterprises we’ve supported before yours. In the end, TaroWorks’ path towards scale will be much clearer and you will have the knowledge, tools, and hopefully, the investment, to get there.”

That’s exactly what TaroWorks needs to grow so I’m looking forward to the experience.

Editor’s Note: This blog post originally appeared on the NextBillion website.

Update: TaroWorks at the GSBI Investor Showcase (August 21, 2018)

POST TOPICS

Sign up to receive emails with TaroWorks news, industry trends and best practices.

TaroWorks, a Grameen Foundation company.

Site by V+V